NEAR the tents of some nomadic tribes may occasionally be seen crude looms on which are woven some of the most interesting rugs that now reach the Western markets. In all probability they are not dissimilar to what were used thousands of years ago, for it would be impossible to construct a simpler loom. Where two trees suitably branching are found growing a few feet apart, all of the upper branches are removed excepting two, which are so trimmed as to leave a crotch at the same height in each tree. In each crotch is rested the end of a pole or beam, and parallel to it is placed another extending at a short distance above the ground from trunk to trunk.

Or, as is more frequently the case, roughly hewn posts are firmly implanted in the ground and horizontal beams are stretched between them. In the upper one is a groove with a rod to which one end of the warp, consisting of strong threads of yarn numbering from ten to thirty to the inch, is attached, while the other end is tightly stretched and firmly secured to the lower horizontal beam. Sometimes the beams to which the warp is attached are placed perpendicularly, so that the weaver may stand and move sideways as the work progresses.

But among a very large number of those tribes that are constantly wandering in search of new pastures for their flocks and herds, it is customary to let the loom lie flat on the ground, while the weaver sits on the finished part of the rug.

Under more favorable circumstances, when the tribes live in villages or cities, the looms are so made that the weavers are not compelled to bend in order to tie the first row of knots or stand erect to finish the last rows of a long rug.

Of the several devices by which the weaver may remain seated while at work, the crudest consists of a plank used as a seat, which rests on the rungs of two ladders placed parallel to each other at the sides of the rug. As the work progresses, the plank is raised and rested upon the higher rungs.

More frequently, however, both upper and lower beams of the frame have the shape of cylinders of small diameter, which revolve between the upright posts. The lower ends of the threads of warp are attached to the lower beam, and the other ends may either be wound several times around the upper one or else pass over it and be kept taut by weights attached to them. Such a loom is generally used for weaving very large rugs, which are rolled up on the lower beam as the work progresses.

Below is represented a loom commonly used in many parts of the Orient. When preparing it for weaving two stakes are driven in the ground at a suitable distance apart, and about them the warp is wound in the way a figure eight is formed. The warp is then carefully transferred to two rods that are attached to the upper and lower beams. If it has been carefully wound, none of the threads should be slack; but if desired the tension may be further increased by different devices.

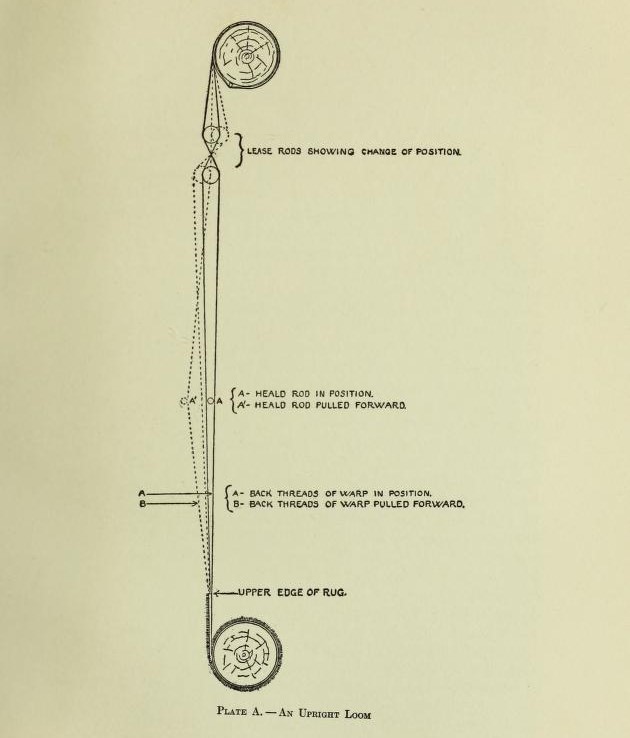

Two other rods, known as ” Healds,” are then attached to the front and back threads of warp; or in the case of a single rod, it is attached to the back threads, as shown in the Plate. A lease rod is next inserted between the threads of warp that cross below the upper beam, and another is placed below it where, if necessary, it is supported in position by loops.

When the weaving begins, a short web is generally woven at the lower end to protect the knots from wear. After the first row has been tied, the shuttle carrying the thread of weft is passed between the front and back threads of warp; the heald rod attached to these back threads is then pulled forward, so that they are now in front of the others, and the shuttle is passed back. If the rug is narrow, only one shuttle is used; but if the rug is wide, or if the weft consists of two threads of unequal thickness, a shuttle is passed across from each side. Every thread of warp is in this way completely encircled by the thread of weft as it passes and repasses.

When weaving large rugs, there is an advantage in having two heald rods, as by their use the distance between the front and back threads of warp may be increased. The object of the lease rod is to prevent any slack caused by drawing forward the threads of warp, and is accomplished in a very simple manner, as will be seen by studying the drawing; since when the tension of the back threads is increased by drawing them forward, the tension of the front threads is also increased by displacing the lease rods which thereby stretches them.

3 Types of Weave Classifications

The products of the loom are divided according to their weave into three separate classes. The simplest of these are the kilims, which are without pile and consist only of warp and weft to which a few embroidered stitches representing some symbol are occasionally added.

A more elaborately made class are the Soumaks. They consist of warp covered by flat stitches of yarn and of a thread of weft which extends across and back between each row of stitches in the old rugs and between each second and third row of stitches in the new rugs. In the narrow, perpendicular lines that define both borders and designs the stitch is made by the yarn encircling two adjacent threads of warp; but in other parts of the rug it is made by the yarn passing across two adjacent threads of warp at the front, and after encircling them at the back, recrossing them again at the front. It is then continued across the next pair of adjacent threads of warp.

The result is that at the back of these rugs each of the two threads of warp encircled by the yarn appears as a separate cord, while at the front the yarn passes diagonally across four threads of warp. As this diagonal movement is reversed in each succeeding row, the surface has an uneven appearance sometimes termed “herring bone” weave.

By far the largest class of rugs are those with a pile. When making them, the weaver begins at the bottom and ties to each pair of adjacent threads of warp a knot of yarn so as to form a horizontal row. A thread of weft is then passed, as often as desired, between the threads of warp and pressed more or less firmly with a metal or wooden comb upon the knots, when they are trimmed with a knife to the desired length. Another horizontal row of knots is tied to the threads of warp; again the yarn of weft is inserted; and so the process continues until the pile is completed.

In tying the knots, work almost invariably proceeds from left to right and from the bottom to the top. It is but rarely that the warp is stretched horizontally and that the knots are tied in rows parallel to the sides. It is still more infrequently that a rug is found in which the knots are tied by working from the center to the right and left, and to the top and bottom. These interesting exceptions may easily be discovered by rubbing the hand over the pile, when it will be noticed that the knots lie on one another so as to face the same direction, which is the opposite to that in which the work of tying advanced, or as is generally the case, from top to bottom.